Why we should make our ideas compete with each other

Ideas are too strong for us to control. Make them compete until the best one wins

Hi all,

Today’s note is on the longer side for a change, so I’ll keep my little introduction brief.

I’m currently watching Stutz, the documentary about Jonah Hill’s therapist.

A key takeaway is that there are three constants in life we need to accept: 1) Pain 2) Uncertainty and 3) Constant Work. The documentary shares tools we can use to deal with these constants.

With that, I hope you enjoy the rest of your day of rest!

—Brendan

We like to think we’re in full possession of our ideas, but more often they’re in possession of us. That’s surprising for something that’s invisible and weightless and comes from somewhere outside of our own head. Whenever I confidently believe I wear the pants in my relationship with my ideas, when I believe that I can easily disown bad ideas or embrace good ones, I remember the below facts:

1) Even smart people can have their independent reason overthrown by ridiculous or dangerous ideas. The brilliant statistician RA Fisher, an avid smoker, could never accept the staggering evidence that smoking caused lung cancer. Linus Pauling was a Nobel Prize-winning chemist who, in his later years, became obsessed with the failed idea that you could treat cancer through mega-ingestion of vitamins.

2) Ridiculous or dangerous ideas can also spread from person to person, like a virus. In 2017, an anonymous online persona named “Q” began posting fabricated claims about American politicians. The false ideas spread and consolidated into what we now know as QAnon. At its peak, some polls estimated that at least several million Americans believed its tenets. On TikTok, viral bad ideas, such as the deadly “blackout challenge”, have been equally rampant.

These facts illustrate the strength and virality of ideas. But they also say something equally fascinating about the mind. If an idea is a stranger shivering outside the house, the human mind is predisposed to generously open the door and welcome him in. Our mind loves inviting in ideas, even if they can and do easily take over the house. That’s because many ideas—free speech, the Golden Rule, “all men are created equal”—are good ones. They’ve helped us successfully survive and reproduce and will continue to do so. We ignore ideas at our peril… and yet we frequently die fighting for them.

We all know someone who has changed for the worse because they’ve been exposed to misguided or prejudiced ideas about what’s real or what’s right or wrong. Because we become like the ideas we believe—and ideas themselves are so powerful and virulent—we should care a lot about how to best evaluate the ideas in our head.

To start, it’s helpful to think of an idea as a meme.

Memes

Richard Dawkins coined the term meme to describe any cultural artifact that spreads between minds. Most of us are familiar with the term meme to describe those funny or relatable images / GIFs we share through the Internet. Those “Internet memes” are certainly a kind of Dawkins-esque meme, but a true meme can be anything that spreads between minds, from songs to catch-phrases to ideas. By Dawkins’ broad definition, all good or bad ideas, such as capitalism, DeFi, antisemitism, Manifest Destiny, effective altruism, and white privilege, are memes. The common denominator between them is that, for better or for worse, they can spread. Like genes, that’s their primary goal.

As Dawkins would suggest, just as our bodies are mere vessels to spread our genes to our offspring, our minds are mere vessels to spread memes to other minds. Daniel Dennett further expounds on this concept in his book Consciousness Explained:

“The first rule of memes, as it is for genes, is that replication is not necessarily for the good of anything; replicators flourish that are good at… replicating! […] [T]here is no necessary connection between a meme’s replicative power, its ‘fitness’ from its point of view, and its contribution to our fitness (by whatever standard we judge that).”

Ideas are just a special kind of meme, and they colonize our minds regardless of whether they benefit us or not. Their entire goal is to just spread to another mind. When a scientist has an amazing discovery, for example, she will immediately feel the urge to share it with a colleague or publish it in a journal. With any luck, that idea will spread, hopefully for the benefit of the scientific community. Conspiracy theories and gossip spread just as virulently through the Internet, but clearly with little benefit to all those minds doing the spreading.

It's almost a riddle. What can’t be seen, can’t be touched, has no mass and yet can drastically harm (or help) the world? Ideas.

Cleaning the Dung Heap

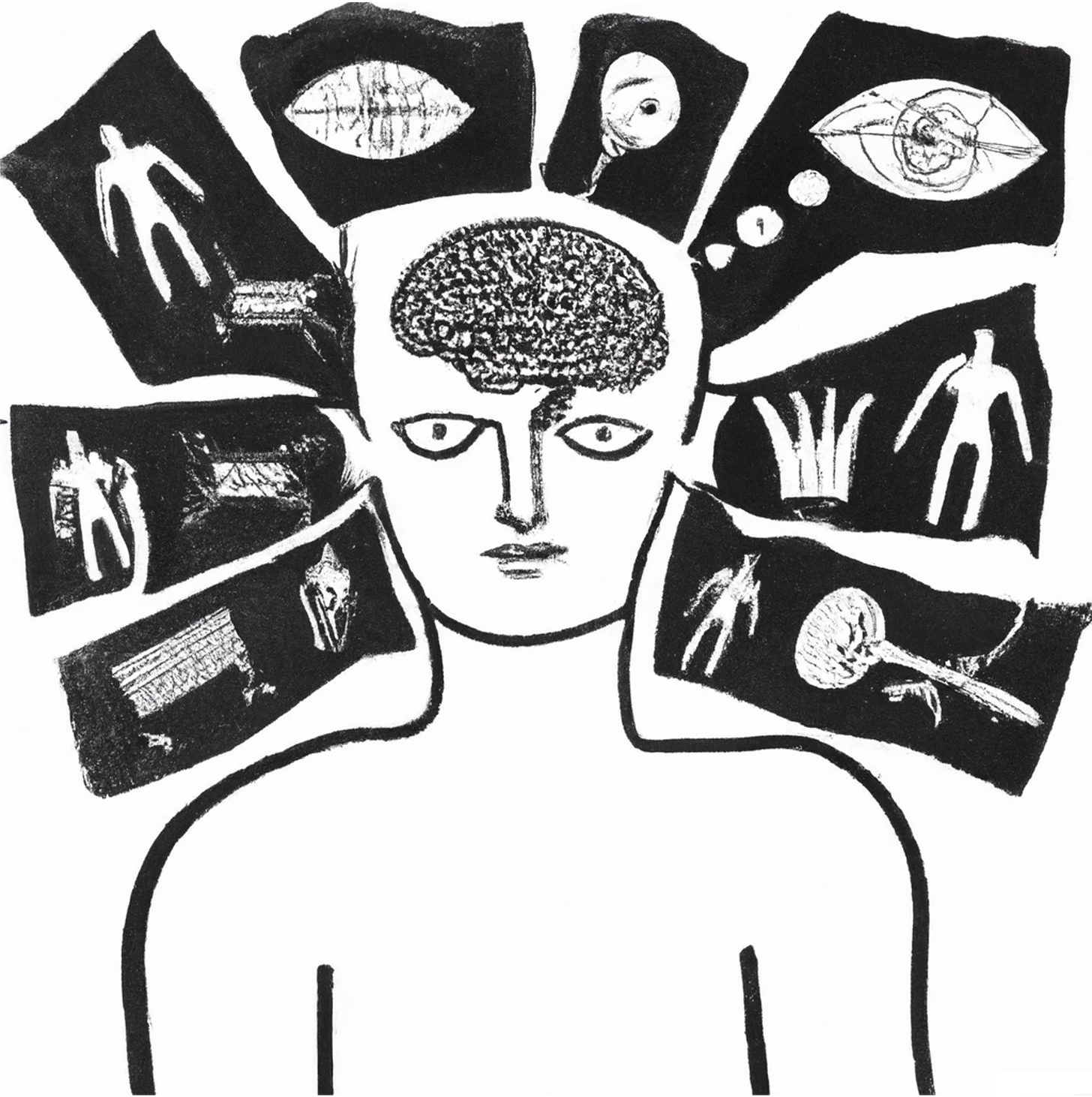

It may be uncomfortable to think of our mind as just some “dung heap” (as Dennett puts it) for hosting and spreading ideas (or memes in general). But it’s true if you think about it. Between work, speaking with friends, and consuming mass media, I’m probably exposed to over hundreds of new ideas every day. I may start believing or spreading some of them without even being consciously aware of it. Can you name the last five ideas you shared with another person? Personally, I can only name one or two. And are you aware of how you came to believe X or Y? Do you remember the book or person who shared that idea with you?

We’re not always consciously aware of the source of our own ideas! And yet these same ideas can have a massive impact on our direction in life. Recall RA Fisher and Linus Pauling, two extremely intelligent people who were taken off course by bad ideas. Or Mike Lazarides, the founder of BlackBerry, who thought it was ridiculous to put a computer on a phone. How wrong he was! We should want to avoid getting trapped by bad ideas, especially those that may have been spread to us from other people without our own awareness. Common examples: buying more stuff than we can afford, over-working to the detriment of our health, cutting ethical corners to get ahead, getting tunnel vision about a particular course of action. More extreme examples, such as falling for conspiracy theories or joining a cult, are not out of the realm of possibility for many people…

One of the best ways to prevent any one bad idea from taking over your mind is to not fight it directly. Instead, you introduce competition in the form of other ideas. As Dennett reminds us:

“Minds are in limited supply, and each mind has a limited capacity for memes, and hence there is a considerable competition among memes for entry into as many minds as possible.”

(Recall ideas are just a special kind of meme.)

By openly exposing yourself to a variety of ideas, you can create and maintain a healthy degree of competition that can prevent one idea from taking over. The way you can tell there is some healthy competition is that it’s actually a bit uncomfortable. When different ideas are competing for your attention and investment, inevitably you’ll get in a situation in which two contradictory ideas face off. This leads to what psychologists call cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance is typically thought of as a bad thing, but I argue that it’s a signal you are creating a healthy environment in your mind. I like to think of this healthy environment as a forest, in which there is some metaphorical competitive balance between species. When this balance is disrupted, as happened in Yellowstone when the wolves were killed off and the elk ravaged the plant-life, the forest declines.

Here is a concrete example of the competition of ideas. I’m not a Marxist, but I recently listened to an interview of Richard Wolff, a Marxist scholar who clarified some of the common misconceptions of Marxism and offered thoughtful challenges of capitalism. I walked away from the conversation feeling uncomfortable. I could feel Wolff’s ideas seeping into my mind and battling with my existing pro-capitalism ideas. I started to wonder whether there could be other economic systems beyond capitalism, a thought that previously seemed untenable. In the throes of competition, my mind opened up, just a bit, to some new ideas.

You might find it difficult to force yourself to read or listen to ideas that you disagree with. This is exactly why Adam Grant recommends we all have what he calls a “challenge network”, a group of people that is tasked with challenging our ideas. If you find it difficult to actively seek out ideas that may compete with your existing ones, you might benefit from outsourcing that activity to other people, your challenge network, who would be more than happy to do it for you.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence”, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

Fitzgerald isn’t suggesting intelligent people vanquish competing ideas or only somehow hold the correct ideas, as impossible as that is. He’s suggesting, as I’m suggesting, that they welcome ideas that may compete and create friction. And may the strongest idea win! A mind with competing ideas is not comfortable, but it is balanced. Leveraging the forces of competition, it’s less likely to be critically wrong. It’s less likely to fall into the traps Fisher, Pauling, Lazarides, and more recently… Kanye West (who likely doesn’t have enough people he respects disagreeing with him).

We don’t always control the specific ideas in our head, but we can make them compete to prove their worth to us.

—Brendan

Further Reading: 1) The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins 2) Consciousness Explained, Daniel Dennett 3) Snow Crash, Neal Stephenson

Thanks for reading! I love when these thoughts lead to conversations with readers. Did you find anything interesting or surprising? Reply to me and let me know.