Hi all,

Summer is *unofficially* here. For those of you in the U.S., have a happy Memorial Day and long weekend!

Today’s article introduces one of my favorite concepts from systems thinking that also happens to be highly relatable. How often do we find ourselves dependent on a crutch to get by? Or more challenging, we become that crutch for someone else?

Let’s investigate how we can build more self-sufficient systems…

—Brendan

📖 The Story

“I’m sorry, it was an unusually tough year for performance reviews. Promotions were… super uncommon.”

The vapid words of corporate consolation hung with Sara as she walked out of the office and into late afternoon sun, dejected. “Super uncommon.” She burned to prove her supervisor wrong.

Last year, she had started managing a new analyst, Amir. “Hi Sara - can you help me troubleshoot this?” The Teams messages would ooze from Amir almost daily. Within minutes, Sara would be on a Zoom call, helping him fix a #VALUE error in Excel.

Everything came to a head when it was time for Sara’s team to produce an annual report to the VP, a herculean effort of spreadsheet wizardry. Amir could not pull his weight. Sara had no choice but to step-in and eat much of his work. It had been her shining opportunity to show she was ready for a promotion. Instead, she had to step-down to do much of the “analyst work.”

Reflecting on this experience, Sara realized a key insight. Amir had become too dependent on her hand-holding to perform adequately. She had become Amir’s crutch, which prevented her from growing her own career.

Going forward, if she can invest her time to train Amir, he will slowly become more independent. She’ll have more time to take on a leadership role, and she’ll earn the promotion that she deserves…

🧠 The Signal

The (fictional) working relationship between Sara and Amir is a classic example of what system thinkers call shifting the burden. Over the year, the burden was shifted from Amir (the source of the underlying “problem”) to Sara, who kept intervening and applying temporary fixes to treat the symptoms. Unknowingly Sara enabled Amir’s dependency. Assuming responsibility of this “burden”, Sara could not progress in other areas of her career.

Shifting the burden isn’t unique to managing people. It can happen any time you try to solve a problem by treating its symptoms instead of its root cause. You don’t really “solve” the problem but shift it to something or someone else.

Here’s how it normally plays out:

The “system” (a company, person, government, car, etc.) is in an undesirable situation.

Instead of fixing the actual underlying problem, which can take a lot of time and effort (boo!), the intervenor, often with good, empathetic intentions (!!), applies an easier, shorter-term fix to address the symptoms (yay!).

The fix works, so when symptoms return, resources are diverted away from fixing the underlying problem to again apply the symptomatic solution.

The system becomes increasingly dependent on the symptomatic solution as fixing the underlying problem becomes more and more difficult.

The underlying problem festers and gets worse.

Shifting the burden is a common anti-pattern in life that you want to avoid as soon as you notice it. As we saw with Sara, it can lead to a spiral of dependency and unintended negative consequences.

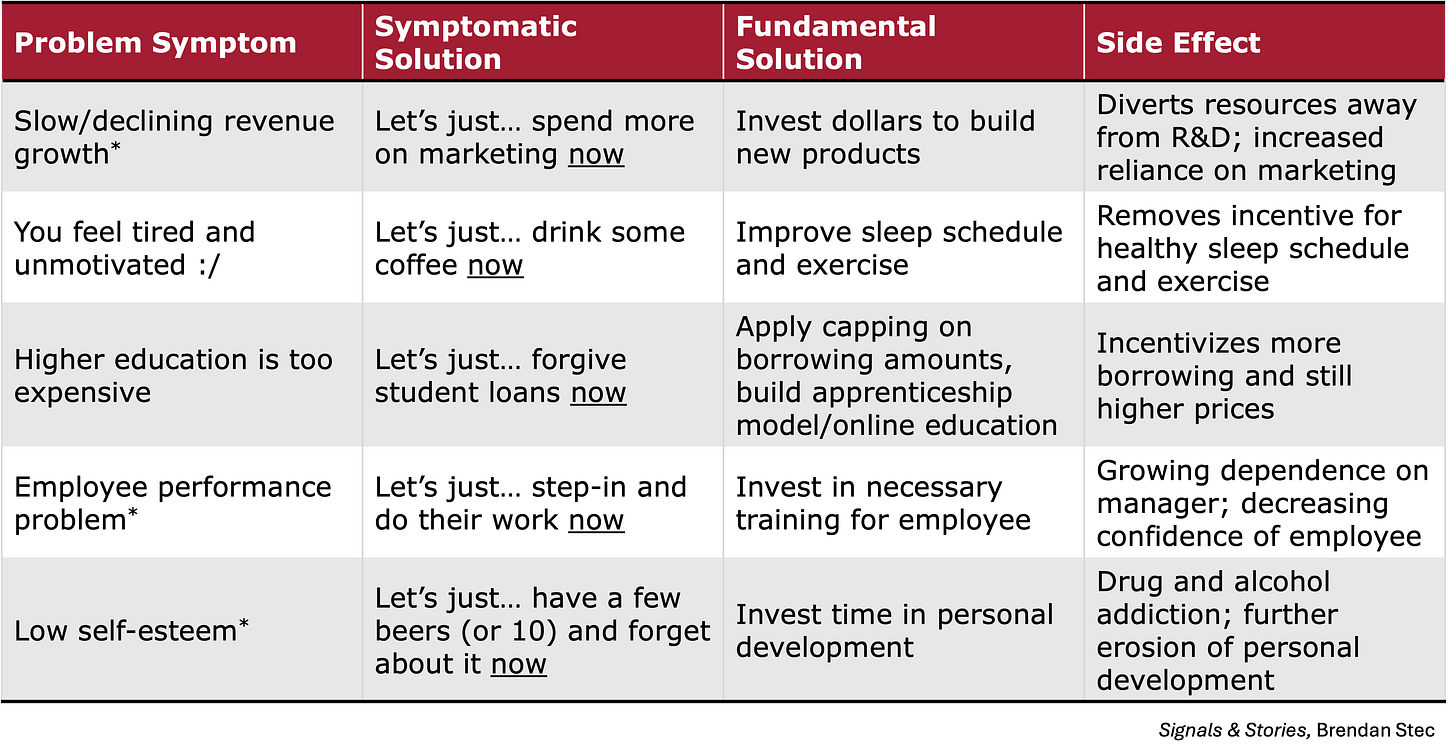

Below are a few examples.

A few observations:

The burden is always shifted to the symptomatic solution, which can enable dependency or addiction.

The symptomatic solution can always fix the symptoms “now”, while the fundamental solution requires more effort upfront to fix the underlying problem “later.” That’s partially why the symptomatic solution is so tempting.

💡Some Prescriptive Advice

How do we deal with shifting the burden?

In Thinking in Systems, Donella Meadows recommends avoiding it from the onset. When you uncover a problem within a “system”—your own body, your team, your business, or whatever—avoid applying a fix that addresses only the symptoms of the problem. Be especially wary that empathy and “feeling bad for people” can lead you to overly-intervene and shift the burden of responsibility from them to your fix. That enables dependency. And get ready for an eye roll but I’ll say it anyway: the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

You can also help a system become self-sufficient. Ask yourself if there are any obstacles that you, as intervenor, can remove to enable self-sufficiency. For example, Sara can teach Amir a new Excel function each week to enable this.

If dependency / addiction has calcified, stop it as soon as you can, as it only gets harder going forward. You will encounter withdrawal as the system must re-learn how to thrive on its own—without the fix.

Here’s a poignant example of avoiding shifting the burden. Helen Keller was born both deaf AND blind. But she was never coddled or made to feel weak as a child. As Daniel Kim of The Systems Thinker writes,

“[I]f it had not been for the determined efforts of her teacher, Ann Sullivan, who refused to let Helen’s handicaps prevent her from becoming self-reliant, Helen probably never would have achieved her real potential.”

Keller maintained responsibility for her own actions in life; they were not shifted to her parents or teachers. Armed with real agency in her life, she felt capable to blaze her own trail. She eventually graduated from Radcliffe College and led a successful career as an author and activist.

How do you experience shifting the burden? Have you ever found yourself in Sara’s shoes, taking too much responsibility for others? Are there any government policies that you feel enable dependency instead of self-sufficiency? How might we address these challenges?

Reply to this email or leave a comment to share your thoughts.

🎓 Further Reading

Thinking in Systems, Donella Meadows: A classic for developing the systems thinking mindset. "Thinking in Systems is required reading for anyone hoping to run a successful company, community, or country. Learning how to think in systems is now part of change-agent literacy. And this is the best book of its kind."―Hunter Lovins

The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge: A management classic on how to develop “learning organizations”, teams that are best positioned to continually grow and achieve their objectives. Systems thinking is a key tenet to learning organizations.

Thanks for reading!

Signals & Stories is a newsletter that explores the recurring patterns we can recognize to make better decisions—in business and life.

If you like Signals & Stories, feel free to share with a friend or colleague.

—Brendan